Each story begins with an idea…

This collection consists of flowers and animals in a variety of materials, art forms, and colors, with the theme of imagination and engagement running through my teaching philosophy

I was particularly struck by Pratt’s (2005) argument that self-reflection makes teachers better by revealing what is often hidden in their practice. For my visual representation, I created a watercolor painting dominated by shades of green, symbolizing growth and transformation. The visible half of the painting features a forest where the colors gradually deepen, representing how understanding and familiarity develop through ongoing dialogue between teachers and students. In the center, a few birds take flight, symbolizing students as active participants in the learning process.

The forest, both in its visual and spatial elements, embodies the boundless possibilities of educational philosophy—an ever-expanding journey of shared exploration. The hidden portion of this painting was created using watercolor and tissue paper to reveal a hidden garden. The garden represents the discoveries of teacher self-reflection - the unseen side of teaching that only comes to light when educators take the time to look inward. Just as a garden contains unexpected beauty beneath its surface, teaching contains depths that can only be discovered through reflection.

Repeating patterns also hold a special beauty. The arts, including dance, can bring mathematics learning to life by making abstract concepts concrete through movement, patterning, and spatial reasoning. With this idea in mind, I created a repeating ginkgo leaf pattern that explores different angles, light, shadows, sizes, and colors to reflect mathematical principles through artistic expression. Leavy (2020) emphasized that movement can be used as a tool of inquiry, and in my work I translated this idea into the organic movement of the leaves-some of the leaves seem to rotate, while others reflect the light in different ways, creating a sense of depth.

I created a drawing inspired by English illustrator Anita Jeram (the author of “Guess how much i love u”)’s storytelling style, portraying a dog and a mouse standing together on an ornate sofa, gazing at a starry sky filled with meteors. The sofa symbolizes the legacy of past artists and theorists—those whose works form the foundations upon which we build contemporary understanding. The animals represent teachers and students, suggesting that only by standing on the shoulders of past can we reach greater creative and intellectual heights.

This painting is done after a visit to the the Philadelphia Museum of Art, featuring abstract mountains and forests that represent the masterpieces I have seen, but within the cool-toned woodlands/clouds are hidden warm-toned flowers and shining moon. These hidden elements symbolize stories and emotions that only reveal themselves when we take the time to look closely-as the docents encourage us to do-through the lens of culture, history, and language.

In this piece, I used watercolor and folded napkins to create blooming, gradient flowers—each one unique in shape, shade, and spread. The napkin, a fragile yet absorbent material, symbolizes how children's minds receive and react to knowledge differently. As the pigments diffuse through each napkin in unpredictable ways, they reveal vibrant patterns that cannot be replicated—just like how no two students think or learn in the same way. The diversity of colors and textures that emerge from this process represents the richness of individual thinking. When placed together, these watercolor blooms form a flourishing garden—each flower distinct, yet contributing to a shared beauty

In my two-part artwork, I explore how children’s creativity emerges when given space to imagine and express. I used blue tie-dye techniques to mimic the fluidity of the ocean—a symbol of unbounded thought and curiosity. In the first panel, layers of gradient blue resemble a vast sea, where folded origami butterflies float above the surface. These butterflies represent students’ spontaneous ideas—fragile yet vivid—breaking free from rigid forms, much like inspiration that arises in a moment of play.

In the second panel, a piece of hand-dyed cloth is shaped into the form of a skirt. This “skirt of imagination” becomes a metaphor for how creativity can be worn, danced with, and owned by the child. Just as fabric flows with movement, art gives children the freedom to move beyond fixed boundaries and dance within their inner worlds. The process echoes Leavy’s (2020) assertion that integrating arts-based approaches nurtures both cognitive flexibility and emotional engagement, inviting learners to become not just receivers of knowledge, but imaginative co-creators of meaning.

As Leavy (2020) suggests, Arts-Based Education allows educators to construct learning environments that prioritize exploration, interpretation, and personal connection. I created a painting featuring a door that represents students’ inner worlds. Outside the door, the environment is gray and dull, symbolizing a lack of creativity. The door itself acts as a defense mechanism—students may initially be hesitant to express themselves.

However, once trust is established, this door can be opened, revealing a vibrant space filled with imagination and creativity. Sunshine and self-expression are essential in this process, highlighting the importance of personalized curriculum design and a deeper understanding of students. More research and communication are necessary to foster an educational environment where students feel encouraged to explore and share their ideas freely.

Leavy (2020) emphasizes music as a research methodology that preserves cultural narratives, making it a powerful tool for analyzing historical events and social movements. By incorporating these artistic approaches, social studies education goes beyond the textbook, allowing students to connect emotionally and intellectually with imaginations. My painting embodies the infinite imagination that music brings to students.

While listening to music, one may appear quiet with headphones on, but in reality, the mind is already passionately envisioning various scenes. Just like the little dog in my painting, imagining itself eating strawberries, I use sound, vision, and touch—incorporating paint and embroidery—to showcase the multidimensional imagination of students.

As Whitelaw (2021) explores, collage provides a dynamic framework for lesson planning by layering ideas, perspectives, and materials. My collage embodies the idea of breaking conventional boundaries in learning. The seamless connection between ocean and sky represents the limitless potential of students when engaged in arts-based, non-linear thinking. The seagulls, freely soaring between these spaces, symbolize students navigating knowledge fluidly, unrestricted by rigid structures. The flowers, vibrant and full of life, capture the unleashed creativity and imagination fostered through artistic expression.

While art may contain elements of prediction, it is the surprises in the imagination that are truly transformative. At the bottom of the image-transfer paintings, I have collaged burnt-out text and grayscale photographs - they symbolize lifeless, monotonous, unimaginative teaching. They represent a world completely dominated by facts, devoid of the surprises that are the point of making art. On this basis, vibrant colors begin to emerge and spread outward as the imagination takes over. As structured words turn to dust, they give way to rotating hues that embody the infinite potential of creativity. Even the most serious buildings and paintings can be visualized as fish, cats, caterpillars, butterflies, and all sorts of things

For my conclusion, I created a handmade zine and a series of stamped bird prints. The birds were cut out during a classroom activity and later transferred using paint and pressure—each print slightly different, bearing the texture of both the process and the paper. On the zine’s cover, a white dove takes flight, echoing the birds within and symbolizing freedom, peace, and boundless imagination. These birds represent the children—each taking off with their own wings of thought, gliding across a sky of possibilities shaped by stories, culture, and creativity. Much like how the printmaking process leaves unique marks with each press, every child carries their own imprint of experience, identity, and learning

This work embodies a fusion of scientific experiments and artistic inquiry that coincides with their discourse on artistic research as a means of deepening disciplinary knowledge. In my work, the use of pink sea salt to create gradient oceans mirrors the ironic process of scientific experiments-similar to how scientists adjust variables and analyze different results. The interplay of different concentrations of watercolor and salt symbolizes how scientific inquiry often leads to different results, just as waves in the ocean change with distance and force. Moreover, the pink feathers I added further reinforce the dual nature of scientific thinking. Like a ship navigating a vast ocean, logic and rational thought guide the way, while imagination and abstract reasoning allow flexibility for exploration and discovery.

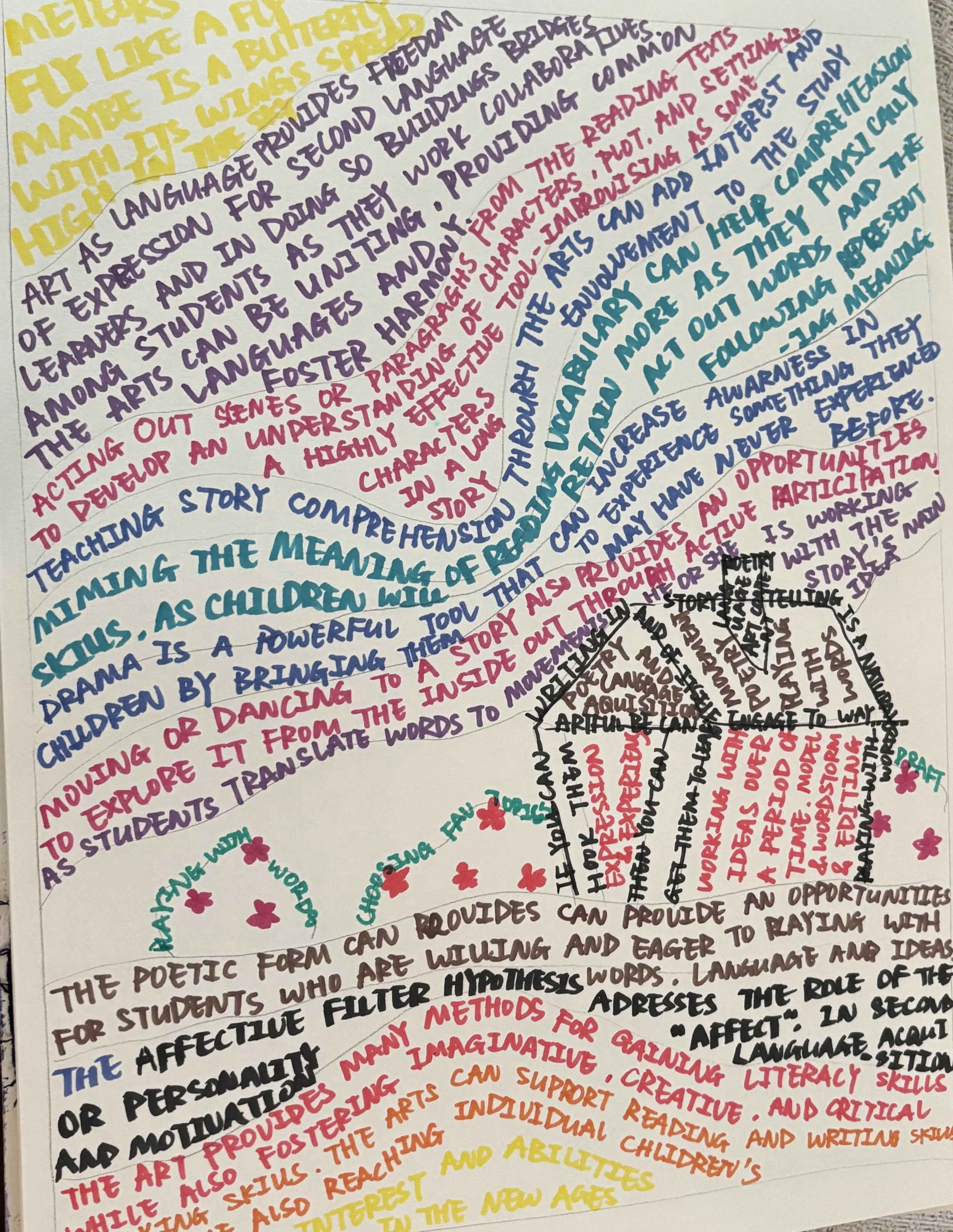

In my own exploration of the significance of poetry and language in art education, I created a painting composed of “letters and words”, symbolizing the “richness of language” and how children are surrounded by an ocean of words and letters. This artwork reflects the idea that poetry demands children to “thoughtfully select appropriate words”, engaging in a process of “reflection and imagination”. In this way, only the most meaningful content finds its place in the "core room" of their understanding — a metaphor for the concepts that truly resonate with them. By integrating poetry into the curriculum, we invite students to delve deeply into language.

I appreciated Grayson Perry’s perspective on sketchbooks being pocket- or handbag-sized, allowing for spontaneous appearance of creativity. Inspired by these ideas, I designed a sketchbook-style collage that diverges from traditional brown-paper books. Mine is colorful, made with vibrant paper cutouts and layers of textured material, reflecting the diverse and creative possibilities of sketchbooks. I also included quotations and definitions that resonated with me. Also, I made a jeans pocket for the sketchbook to indicate that it can be carried around to recap the inspiration for us.

Inspired by Dear Data (Lupi & Posavec, 2016), I designed a postcard that visualizes a week of noticing “hidden beauty” through symbols of spring—flowers, leaves, and colors. Each element on the front of the postcard represents a specific moment: the warm smell of morning coffee, the floral scent of freshly washed clothes, the softness of sunlight on my skin, and the simple joy of seeing a stranger smile.

On the back of the postcard, I annotated each flower or leaf with a description of what it stands for, connecting data with emotion and memory. By observing and recording subtle sensory experiences, I became more attuned to the aesthetics of my everyday life. My data story is not about numbers alone, but about meaning—an embodied archive of fleeting, beautiful encounters.

Sketchbook reflection

Exploring Critical Art-Based Practice and Arts Integration

Over the past few weeks, preparing my sketchbook has become more than just a creative exercise; it has become a powerful journey of self-reflection, critical inquiry, and pedagogical exploration. Through each sketch, collage, watercolor, and paper strip, I found myself thinking about issues far beyond aesthetic choices. The sketchbook became my living space where I grappled with how art can facilitate profound meaning-making in K-12 classrooms and how artistic practice can be a vital bridge between knowledge, emotion, identity, and community.

At the core of my experience has been a deepening understanding of critical arts-based practices. Initially, my aim in using sketchbooks was to record ideas visually. However, as I experimented with different mediums - multi-layered collages, symbolic gardens, transformative paintings - I realized that making art is more than just personal expression; it is a way of thinking critically about the world (Taylor, 2014). Implicit in every image I create are questions: What am I assuming? Whose story am I telling? How do the materials shape the meanings I construct? The shift from “creating for self-expression” to “creating for critical reflection” has shown me how art practice can open up important conversations about voice, culture, history, and power in the classroom setting.

This experience also deepened my understanding of arts integration at the K-12 level. In making sketchbooks, I naturally crossed disciplinary boundaries: visualizing mathematical patterns through drawing, exploring emotional narratives through color, and connecting literary themes to symbolic imagery. I began to imagine how students could do the same - using visual metaphors to understand scientific cycles, illustrating historical events through collage, or creating magazines to synthesize social studies (Eisner, 2002). I realized that true arts integration is not about adding art as decoration outside of the curriculum. Rather, it is about using art as a language for deep interdisciplinary inquiry. In this model, students don't just learn about art, they learn through art, developing skills such as critical thinking, empathy, and resilience along the way.

However, my journey has not been without challenges. One of the main questions I face is How do I balance openness with structure? At times, the freedom of the sketchbook overwhelms me. Faced with endless possibilities, I sometimes question what is “good enough” or worry about the coherence of my ideas. Greene (1995) also emphasizes that imagination needs both the freedom to roam and the guidance to be meaningful. The conflict reflects a common challenge in the classroom - how to give students enough freedom for meaningful exploration without letting them get lost or disengaged. I began to realize the importance of designing intentional yet flexible frameworks: providing guiding questions, thematic prompts, or common inspirations that offer a foundation for students though also leaving enough room for individual exploration.

Another barrier that emerged was the issue of representation and inclusivity. The crafts I make are inspired by my personal experiences and cultural background, and I especially wanted to create sketchbook prompts that would remind everyone to be inclusive of everyone’s stories and backgrounds when learning. The art-based critical practice is to figure out which stories are the most important and which stories have been pushed to the sidelines. This reflection prompted me to think more carefully about how to choose materials, artists, and themes that are culturally sustaining and inclusive, rather than defaulting to mainstream or familiar references.

Finally, they thought about the question of evaluation. How can we take into account the deeply personal and process-oriented nature of sketching while respecting its program-based framework in a framework that requires both scoring and standardization? Through my own frustrations and breakthroughs, I understand that sketching is actually a place for ongoing dialog and growth. It should not be measured only by technical skill and regarded as a finished work. Reflective dialog, peer feedback, and process archives seem more in line with the goals of critical art practice than traditional grading rubrics.

Ultimately, the process of developing this sketchbook has inspired me to recognize that art is not a field separate from academic learning, but rather a core, critical mode of inquiry that deserves a meaningful place in the K-12 classroom. It reminded me that creativity is inherently political and relevant-every choice of color, texture, and metaphor has the potential to influence how people see the future. Moreover, these choices have the potential to influence how students see themselves and their world. It reinforces my belief that it takes courage to teach art: courage to embrace uncertainty, to trust the messy creative process, and to center student voices in all their complexity and beauty.

In conclusion, Using sketchbook to record my ideas has been a fun process and habit. As I move forward as an educator, I carry with me not only a fuller sketchbook but also a fuller understanding of what it means to teach with heart, imagination, and critical consciousness.

Reference

Greene, Maxine (1995). Releasing the Imagination: Essays on Education, the Arts, and Social Change.

Taylor, Pamela G. (2014). Art-Based Research and Pedagogy.

Eisner, Elliot (2002). The Arts and the Creation of Mind.